Ultimately, sustainability can only be built on the transformation of human character. The brilliant John Elkington did a great job by presenting three dimensions of sustainability – economic, environmental and social (people, planet and profit). Its becoming ever more clear, that the myopic pursuit of economic sustainability alone, is ironically, unsustainable. Or to put it another way, its getting hard and harder to make a buck for most people. Our economic systems are getting more and more complex and encumbered by their own dysfunction. And consequent erosions of social and environmental systems compound the dysfunction.

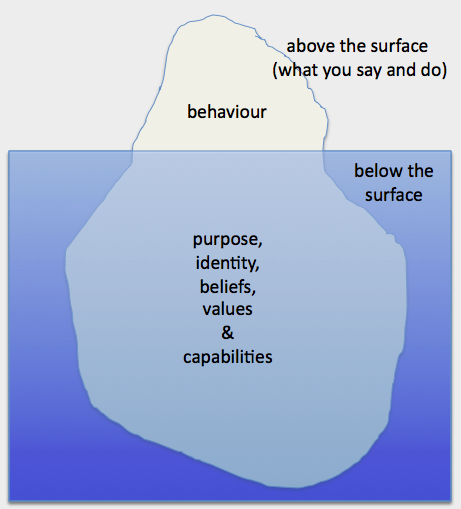

The iceberg model

Sue Knight’s iceberg principle indicates that the behaviours we get (what people say and do) is determined by what is below the surface (purpose, identity, beliefs, values and capabilities). You can’t change behaviour sustainably without changing the sub-surface drivers. I have road-tested this model over the years with observation of human behaviour (including my own) and I find it it be very useful. The remainder of this blog is predicated on the iceberg as an excellent model of human behaviour. It is applied here not just for explaining individual behaviour, but also for the behaviour of collectives, such as corporates. If your not convinced, you can exit here or maybe comment on the validity of the model.

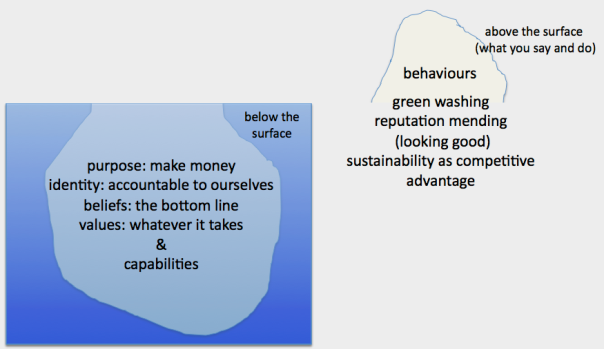

The fractured iceberg

Where sustainability behaviours artificially overlay a conventional culture of myopic profit pursuit, the iceberg is fractured. The old “beneath the surface factors” aren’t compatible with true sustainability and the resulting behaviours include green washing and reputation-mending. I suspect that even overlaying the more enlightened strategy of sustainability as a competitive advantage will not be truly sustainable until the sub-surface drivers change. Internal forces will continue to generate company behaviours compatible with the old drivers.

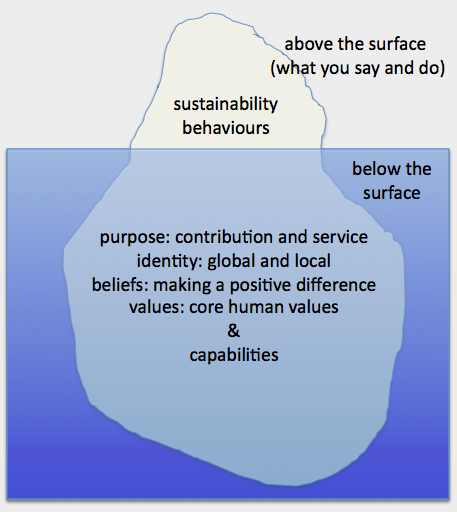

The sustainability iceberg and transformation of character

True sustainability will naturally emanate from below the surface sustainability drivers such as those in the diagram below. Motives of extraction and exploitation will be supplanted by those of contribution and service. (The examples of purpose, identity, values, beliefs and capabilities used here are arbitrary and could be replaced by others.)

The drivers that underpin sustainability will translate, over time, to the transformation of character. But can we change? We definitely can! For eons, humanity has been driven mostly by survival drives (see my blog on The End of Empires). When the survival drive is our default mode, more elevated and altruistic expressions of character, innate in humans, are suppressed.

As more of us begin to see that our ancient embedded drives are actually counter-productive, and compromising our survival, I believe we will refine our character and generate sustainability drivers for the benefit of our businesses and communities. An exciting prospect is the reinforcing nature of this virtuous cycle. As we improve character, a more sustainable environment is a more compatible ecosystem to work and live in. Over time, we learn that sustainability is in our self-interest. As we reach a tipping-point where these drivers become more common, there will be multiple unintended beneficial outcomes.

The evidence.

So does this sound too optimistic? I believe there is strong evidence to support this position. In the interests of brevity, here are two examples.

Jeremy Riftkin’s RSA Animate video anticipates “the empathic civilisation”. He argues that we are wired more for empathy than competition.

There is a rich vein of evidence that a more human focussed approach to running business generates better outcomes than older command and control models. A recent paper from the Maritz Institute posits that “Outdated beliefs about human action and interaction hold us in a transactional model of engagement.” Their paper links “the new normal” to a enlightened understanding of human drivers and interaction. These support better stakeholder engagement and (I would add) sustainability.

“A new framework for stakeholder engagement is needed … a framework anchored in the latest research relative to human drives and behavior. The goal of this framework is to create better business results that, at the same time, enrich stakeholders in ways that are most meaningful to them. It is about building a win-win proposition … Better Business. Better Lives”. (from The Game Has Changed, Maritz Institute)

Let me know if you think we are on the road to achieving this – or not.