There are a belwildering array of sustainability ratings – but what do we believe? How do we know they are measuring and evaluating the right things?

In their Rate the Raters documents, SustainAbility identified over 50 sustainability rating agencies. SustainAbility will offer insights into how credible each rating system is, but I suspect that many imponderables will remain. For example, in part two of the study, the Dow Jones Sustainability Index was ranked highest in credibility by the study’s participants. But in his article titled, When Pigs Fly, RP Siegal noted with incredulity that Haliburton is now listed in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index.

Here are two reasons that determining a company’s sustainability will remain problematic:

- the bureaucratisation and commercialisation of quality processes

- determining sustainability

The bureaucratisation and commercialisation of quality processes

In the galaxy of organisation endeavour, sustainability reporting can be regarded as a quality measure. For example, while the ISO 9000 series deals with operational quality matters, the ISO 14000 series deals with environmental management. While ISO 14,000 may not be classified as sustainability reporting, it serves the same purpose, in that it provides third party assurance of a quality measure.

I like Tom Peters perspective on quality. He quotes Richard Buetow, a Motorola executive.

With ISO 9000 you can still have terrible processes and products. You can certify a manufacturer that makes life jackets from concrete, as long as those jackets are made according to the documented procedures and the company provides next of kin with instructions on how to complain about defects. That’s absurd.

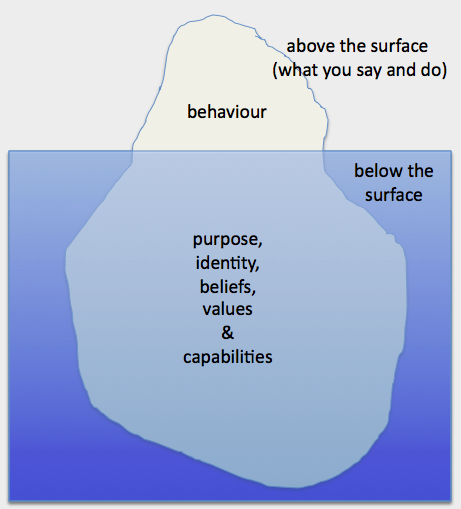

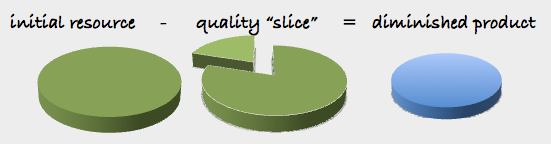

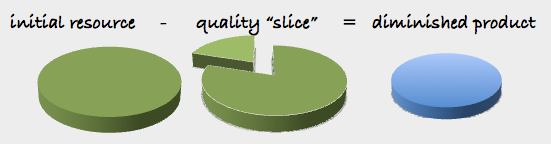

Where quality processes are formalised, they can divert resources from the product or service itself. Any product or service will justify a finite amount of resource input, so ideally, any quality process will add value equal to or greater than its cost. Too often, compliance-driven quality processes militate against quality as they divert resources away from product or service delivery. This is a big issue in service delivery sectors such as education and health. When teachers spend more time on quality assurance processes, they spend less time on preparation for delivery. It may be that, unless there is a compelling reason to get third party assurance, that resource is best invested in enacting sustainability aspirations, rather than measuring them.

I’m not arguing against quality processes – but I am stressing that they have to add value. Sustainability reporting processes will add value to the economic bottom line where there are game-changing benefits. For example:

- a supplier demonstrating conformance with a client’s ESG (environmental, social, governance) standards to ensure continuance of business

- securing a listing in a sustainability index

- remediating reputation losses.

But unless there are clear benefits from quality process third party assurance, why bother?

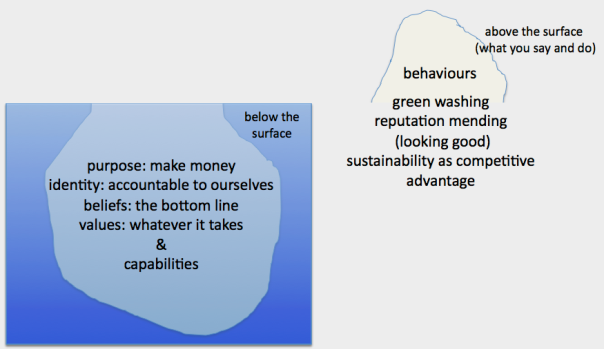

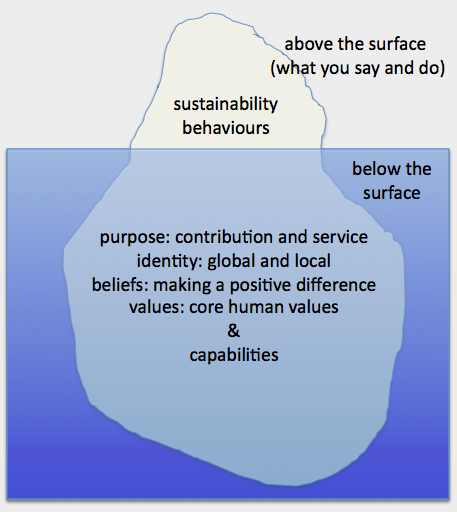

BP’s gulf oil spill illustrates this issue. Along with Shell, BP scored consistently highly in GRI (Global Reporting Initative) reports, and I believe the company’s leaders had, and have, genuine sustainability aspirations. BP invested a lot in rebranding as “beyond petroleum.” But the gulf oil spill incident has undone a lot of the energy BP had invested in sustainability initiatives. What the GRI couldn’t assess, were complex embedded processes, such as the quality of engagement between BP and its suppliers, and the impact of budgets and deadlines on safety and operations.

Commercialisation

No doubt ratings agencies are also well motivated, but budget pressures will typically create pressure to grow the business and perhaps make processes than they need be. SustainAbility’s Rating the Raters cites commercial pressures as an impediment to more transparent report, partly because the raters are paid by those being rated.

Determining sustainability

Part two of this blog will explore what sustainability means in different industries, and from whose perspective.